The Garden Path

This item appears on page 51 of the January 2017 issue.

This is the second in a series of three articles on gardens in Sicily. I visited the island at the bottom of Italy’s boot in June 2016. (See part one, Nov. ’16, pg 51, as well as the Feature Article, Oct. ’16, pg. 32.) — YMH

Florence Trevelyan’s legacy in Taormina

(Part 2 of 3 on Sicily)

Before traveling, I spend hours searching on the Internet and leafing through guidebooks and gardening books trying to match my itinerary with a possible garden, or gardens, to visit. What I’m looking for is not just any garden, no matter how lovely, but one that fulfills a personal criteria.

It must be a garden with a story to tell, a garden that could be nowhere else than where it is and, if at all possible, one that reflects the gardening passion of the person who created it.

On such a search prior to a June 2016 group tour of Sicily, with an “Aha!” I came across Florence Trevelyan’s garden in Taormina, Sicily. Here was a “Garden Path” story with the earmarks of all three requirements!

But who was Florence Trevelyan?

Numerous sites on the Internet provided scintillating, yet conflicting, details about how and why this young English woman from Northumberland, England’s northernmost county, traveled to Sicily in the late 1880s and never returned home.

Choosing bits and pieces and putting them together, here is the account that pleases my gardening and storytelling imagination the most.

The sight of Isola Bella

Although Florence was often referred to as Lady Trevelyan, as the daughter of a son of a baronet, an official “Lady” she was not.

When Florence was but a small child, her father committed suicide. Her mother, Catherine Ann, moved the family to nearby Hallington. There she and, later, Florence, as she approached adulthood, developed a keen interest in establishing “pleasure gardens,” gardens open to the public for recreation and entertainment.

While Florence was not official aristocracy, as a Trevelyan she was “well connected” — so well connected that she was welcomed into the household at Balmoral, where Queen Victoria fostered her growing up, in particular sharing with the young Florence her passion for dogs and plants.

So it continued until a dalliance between Florence and Edward VII, Victoria’s eldest son and heir to the throne, came to the queen’s attention. She was not amused.

Florence was banished not only from court but from Britain. Bankrolled by the queen’s order to pay her an allowance of 50 pounds a month, Florence embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe.

As our tour bus wound its way into the mountains toward Taormina, it was no wonder to me why Florence decided to remain in this small corner of Sicily. Views over the Ionian Sea were spectacular.

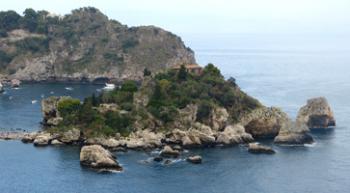

Upon approaching the perched town, at my request we paused by the side of the road so I could take a look at Isola Bella, a rocky outcropping that is attached to the mainland by a swath of pebbled beach when the tide is low, which it was that day.

Isola Bella, “Beautiful Island,” was so named by Florence. Soon after her arrival in Taormina, she bought the rocky outpost, built a small house near its summit and set about establishing a garden of Mediterranean native plants interspersed with exotic shrubs and grasses.

Delighting in the bird life attracted to the island, she became an outspoken pioneer for Italian bird habitat conservation. Isola Bella today is a designated protected natural site administrated by the Italian branch of the World Wide Fund for Nature. When the tide is favorable, visitors can walk across the connecting pebble beach and take a look around the island.

The setting of Hallington Siculo

Some accounts give the date as 1890 that Florence married Taormina’s wealthy mayor, Salvatore Cacciola, and moved from the island into town. Cacciola gifted his bride with a parcel of land exquisitely positioned on a terrace overlooking the sea. Immediately, Florence embarked on the creation of another garden, Hallington Siculo, “Sicilian Hallington,” in memory of her Northumberland gardening pursuits with her mother.

With more than its fair share of grand palazzi, grandiose churches and cozy osterias, not to mention a magnificent third-century-BC Greek theater right in the middle of town and a breathtaking setting overlooking the sea, Taormina is too good to remain touristically unspoiled. On the day of our visit, throngs elbowed their way down the Corso Umberto, the shopping street that cuts through the town’s center.

With a sigh of relief, I left my traveling companions to their window-shopping while I made my way down blessedly nontouristed, cobbled side streets to Hallington Siculo, known today as the Villa Comunale, a public garden. There locals arrive to stroll a bougainvillea-edged promenade overlooking the sea and sit in the sun while bambini run about in a tiny playground.

Florence’s horticultual efforts remain most intact in the northern end of the garden, where there are plantings of native species interspersed with exotic, tropical flora flourishing in a nucleus of trees — olives, pines, cypresses, palms… .

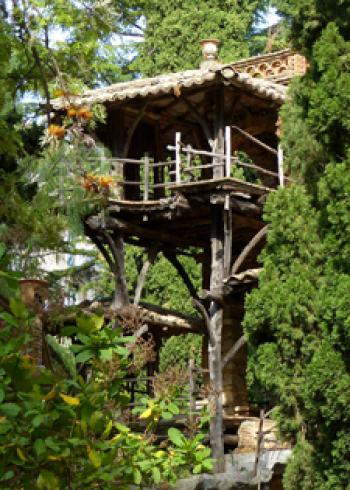

Most astonishing there, however, is her collection of “Victorian follies,” eccentric pavilions constructed from what appear to be architectural salvage — stone, brick, pipes, bamboo, lava rock and pieces of lumber.

Wondrously gimcrack — and multistoried, with balconies, verandas and flights of steps going nowhere — their sole purpose was atmosphere. One can imagine the follies strung with lanterns on a summer evening, guests milling about, music wafting through the garden.

It is said that on more than one occasion Edward VII was in attendance… but only after Victoria’s death.

Hallington Siculo, Taormina’s public garden, is open 9 a.m. to midnight in the summer and 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. in the winter. There is no admission charge.

Email Yvonne Michie Horn at yhorn@sonic.net. Also visit www.thetravelinggardener.com.