Culture shock and wiggle room

This item appears on page 72 of the December 2008 issue.

Many Americans board a plane for an overseas destination without fully realizing that they are flying into a completely different culture. Some experience culture shock: a psychological disorientation caused by immersion in a place where people do things — and see things — differently.

Most cultural groups develop separately, with their own logical (as far as they’re concerned) answers to life’s basic needs. While every culture is ethnocentric, thinking ‘We do it right,’ it’s important for travelers to understand that most solutions to life’s problems are neither right nor wrong. They are different. That’s what distinguishes cultures. And, for a traveler, that makes life interesting.

Americans, like all groups, have their own peculiar traits and ways of doing things. It’s fun to look at our culture from a wider perspective and see how others question our sanity.

For instance, we consider ourselves very clean, but when we take baths, we use the same water for soaking, cleaning and rinsing. (We wouldn’t wash our dishes that way.) The Japanese, who use clean water for every step of the bathing process, might find our ways strange or even disgusting.

People in some cultures blow their noses right onto the street. They couldn’t imagine doing that into a small cloth, called a hanky, and storing it in their pocket to be used again and again.

Once when I was having lunch at a cafeteria in Afghanistan, an older man joined me to make a point. He said, “I am a professor here in Afghanistan. In this world, one-third of the people use a spoon and fork like you, one-third use chopsticks and one-third use fingers, like me. And we are all civilized the same.”

Toilet paper (like a spoon or a fork) is another Western “essential” that most people on our planet do not use. What they use varies. I won’t get too graphic here, but remember that millions of civilized people on this planet never eat with their left hand. (Some countries such as Turkey have very frail plumbing, and toilet paper jams up the WCs. If the wastebaskets are full of dirty paper, leave yours there, too.)

Too often we judge the world in terms of “civilized” and “primitive.” I was raised thinking the world was a pyramid with the United States on top and everyone else trying to get there. I was comparing people on their abilities (or interests) in keeping up with us in material consumption, science and technology.

My egocentrism took a big hit when my parents took me to Europe. I was a pimply teenager in an Oslo park filled with parents doting over their adorable children. I realized those moms and dads loved their kids as much as my parents loved me. And it hit me that this world is home to billions of equally precious children. From that day on, I was blessed. . . and cursed. . . with a broader perspective.

Over the years, I’ve found that if we measure cultures differently (maybe according to stress, loneliness, heart attack rates, hours spent in traffic jams or family togetherness), the results stack up differently. It’s best not to fall into the “rating game.” All societies are complex and highly developed in their own ways.

Just as we have a stereotypical view of most of the world, most of the world sees us as a version of Uncle Sam. To the average Abdullah on the street — who’s seen plenty of American movies, TV shows and tourists and has read countless news stories about those crazy Yankees — we are outgoing, hardworking, informal, rushed, overconfident and unconcerned with class distinctions and authority.

Some of these traits are positive and others aren’t. Remember, there is no absolute good and bad when it comes to comparing lifestyles. For instance, while we may proudly ignore class ranks and think of our friendliness as a virtue, someone from India might be shocked at our “class ignorance,” and a Frenchman might see our “good ole boy” slap-on-the-back warmth as downright rude.

If a prescription could be written to cure culture shock, it would include the following instructions:

• Learn as much as you can about your host culture.

• Assume “strange” habits in this “strange” land are logical. Think of these habits as clever solutions to life’s problems.

• Be militantly positive. Avoid the temptation to commiserate with negative Americans. Don’t joke disapprovingly about a culture you’re trying to understand.

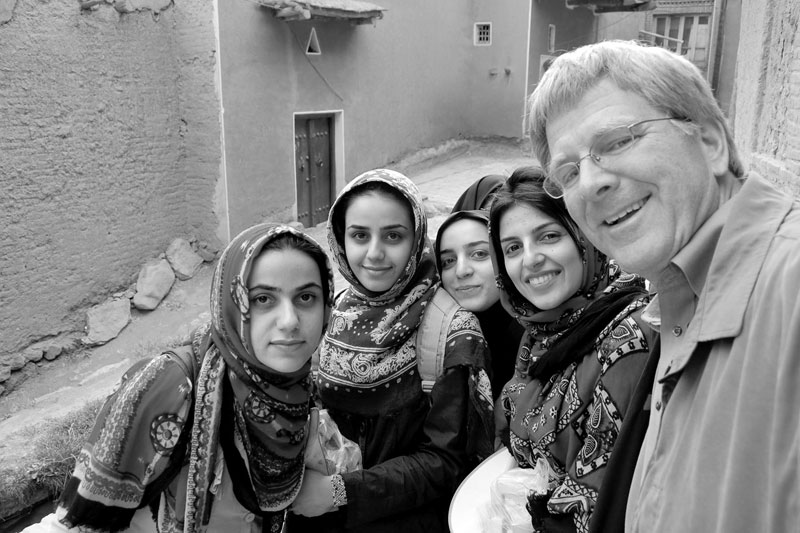

• Make a local friend, someone you can confide in and learn from.

Most importantly, remember that different people find different truths to be “God-given” and “self-evident.” Things work best if we give everybody a little wiggle room. And that goes for more than just travelers.