Walking Norway’s western fjords

—by Yvonne Michie Horn, Santa Rosa, CA

The stones were rough cut — some much larger than others, some demanding a bit of a stretch to get to the next — but each had a worn spot where one’s foot just wanted to go. The stones meandered in a sort of staircase, and indeed that is what they are, placed by 12th-century Cistercian monks to ease a steep portion of the 3,000-foot climb between their monastery on the banks of the Sorfjorden and the plateau high above.

Did the monks organize themselves into a sort of ecclesiastical chain gang and quickly put them in place? Or perhaps it was the duty of every monk heading up from the Sorfjord-en to hoist an additional stone until — whatever is the Norwegian equivalent of “Voila!”— it was eventually done.

It was not only the Cistercians’ feet that wore smoothness into the 616 stones, although they had 327 years to do so. Fishermen, hunters and trekkers have used the steps as a route into the Hardangervidda Plateau, now Norway’s largest national park, for hundreds of years. Our boots were but the latest in the centuries-old parade.

A Country Walkers tour

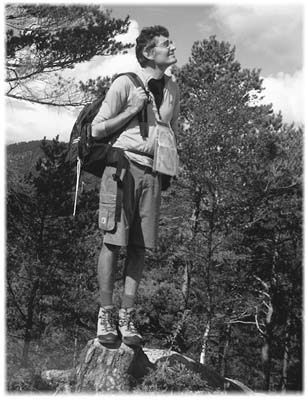

With 12 others, I was traipsing through Norway’s lacy network of western fjords on a Country Walkers itinerary as much devoted to revealing the culture of the country as to a leg-stretching adventure.

It was on day five of our 7-day trek that we reached the mist-drifted plateau, with guides Vidar Rasmusen and Arjen Meurs leading the way, to spread our picnic by the edge of a rushing stream. The rush of water eventually becomes the well-named Skrikjo (which translates to “Shriek”), a waterfall that if not divided by a rock interference would be the highest in the world.

Skrikjo helps water the orchards of Hardanger that stretch for miles along the Sorfjorden. Our picnic included Hardanger cherries grown plump and sweet in the long, far-northern days of summer. (Busy monks, those Cistercians; they not only lugged about stones but planted the Sorfjorden’s first orchards.)

“Norway: Bergen & the Western Fjords” was a recent addition to the dozens of treks offered by Country Walkers, a Vermont-based company that takes seriously its motto: “Explore the world one step at a time.”

On this trip, our first steps took us through Bergen’s historic center, a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site that stretches beside the city’s inner harbor, Vagen, the vortex of Bergen since its beginnings.

Bergen

Following a city guide, we visited sites that the German Hanseatic merchants, who made Bergen one of Europe’s great entrepôts during the 15th century, would easily recognize today: the fortress of Bergenhus, with its burly Rosencrantz tower at the harbor mouth; the pointed gables of the Bryggen (old wharf), with the Hanseatics’ surviving offices and warehouses which line the north quay, and the incomparable setting of the city itself, the front facing the sea, the back cradled in the arms of seven mountains.

Each first Sunday in June, thousands of Bergeners take to these mountains with the goal of bagging all of the peaks in a single day. We took on but one, feeling a bit guilty about abandoning “one step at a time” so soon to board the Floybanen, the funicular that whisks passengers to the top of Mount Floyen for a bird’s-eye view of the city, its surrounding fjords and the silvery shimmer of the Norwegian Sea beyond.

Our city walk was but a warmup for the next day’s trek deep into the Bergen Norwegian Arboretum’s 125 acres of perennials, shrubs and trees incorporated into rocky gorges and mossy hills along the Fanafjord. Here, following our picnic lunch, Vidar and Arjen disappeared behind a large boulder to come dashing out in their Speedos and dive into the fjord.

“When you see the sea, you have to jump in!” Vidar jubilantly explained as he dried off from what is evidently not just a Norwegian thing to do as Arjen, a Hollander, expressed equal enthusiasm for his icy laps. Rising to the bait, one of our group stripped down to her undies for an in-and-out, yo-yo performance she never volunteered to repeat again.

Exploring the countryside

It is the rare Norwegian, from commoner to king, who doesn’t tramp about their unspoiled countryside. The right to do so is ensured by the 1957-enacted Lov om Friluftslivet (Outdoor Recreation Act): “At any time of the year, outlying property may be crossed on foot, with consideration and due caution.”

Shouldering their rucksacks, they stay in hyttes, cabins or lodges located at the crossroads of the country’s extensive network of trails.

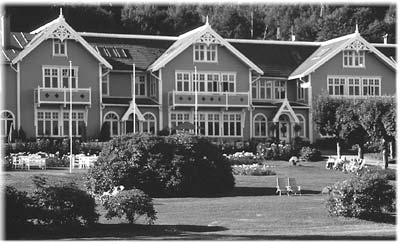

With “consideration and due caution,” we approached not hyttes but two luxurious country hotels for our overnight stays. Our first, Solstrand Hotel & Bad (phone +47 56571100 or visit www.solstrand.com), has welcomed vacationers for over 100 years at its idyllic location overlooking the Bjørnefjord. Borrea Schau-Larsen, the third-generation proprietor of the family-owned hotel, greeted us, saying that she, too, not only enjoys a good walk but also shares Arjen’s and Vidar’s zeal for leaping into the fjord, which she does every Wednesday with friends.

“Blowing and snowing, no matter. We jump in. And it is good!” she said.

Hotel Ullensvang (phone +47 53670000 or visit www.hotel-ullensvang.no), owned by the Utne family since its founding in 1846, headquartered the second half of our trip. Located in the village of Lofthus on land claiming a long stretch of the Sorfjorden’s eastern shore, it was here that the 19th-century composer Edvard Grieg found inspiration for many of his compositions. His “composing cottage,” described by a contemporary as no more than a wooden box with a piano and a stove, remains in the hotel’s garden.

One evening after dinner, we walked through the stillness of the village to Lofthus’ 12th-century stone church for an organ and piano concert featuring, of course, works by Edvard Grieg.

Grieg traveled the Hardanger on foot and horse with internationally acclaimed violinist Ole Bull, “the Nordic Paganini,” the two finding themes for their music in the region’s centuries-old melodies and traditions.

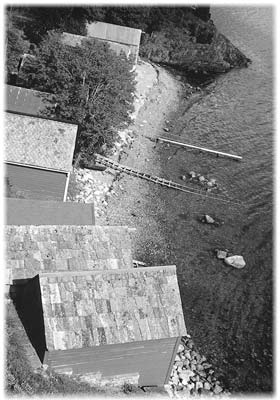

A short ferry ride delivered us to Lysoen Island, where we walked the 13 miles of trails that wind their way through fjords and fauna to end up at Ole Bull’s idiosyncratic house, a mixed-up architectural gem in which Moorish flavor marries Norwegian simplicity.

One day’s walk followed a fjord-side path to the village of Os to visit the boat works, where the light, flexible, fast and strong Oselvar boats, used along the Norwegian coast for nearly 2,000 years, continue to be crafted. Another day’s trek included a visit to a 12th-century stave church, of which but 29 of the original 750 ornately carved structures survive to be listed among the world’s oldest wooden buildings.

Before dinner one evening, while at Solstrand Hotel, Jan Boettcher, an acclaimed rosemaling (rose painting) artist, stopped by to share examples of the artistry with which Norwegians have decorated their furniture and implements since medieval times.

“I learned from my grandfather, who learned from his father, who learned from his father,” she said, adding that only recently have women entered the rosemaling generational train.

Bondhus Valley

At Olaloa, a traditional farmhouse, lunch of perfectly poached salmon, freshly pulled from the sea, boiled potatoes, just emerged from the earth, and a salad of greens, harvested from the farm garden, awaited — fuel for a walk into the Bondhus Valley.

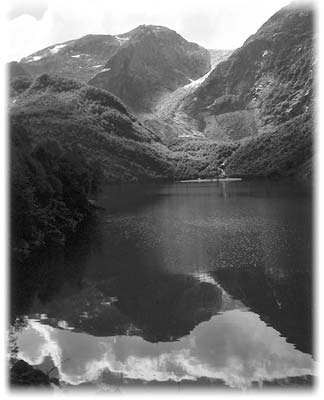

We followed the cascading rockiness of the rushing Bondhus River to the mirror reflections of Bondhus Lake, with the blue and green ice of Bondhus Glacier streaming out of the mountain ahead. All were indications that “Bondhus” is far from a new name on the edge of the Maurangsfjorden.

Reaching the lake, we were given the option of rowing across with Arjen manning the oars or continuing on toward the glacier via the lakeside path with Vidar in the lead. This was yet another example, as with every day’s walk, of options made available for varying levels of hiking endurance and interest.

Had it been May 17 instead of mid-August, Bondhus Glacier, an arm of the famed Folgefonn, would have been dotted with skiers in national costume annually celebrating their country’s ice floes with a day devoted to skiing across them — risky business, it would seem, given the cautionary signs we encountered warning of the glacier’s deep and wide crevasses hidden under covers of snow. With almost equal Norwegian derring-do, Arjen and Vidar jumped into the waters of glacier-fed Bondhus lake, emerging to jubilantly announce, “Ahhh, that was good!”

Our trip ended where it began, in Bergen. Looking at the map, our boots had not taken us far from the “Gateway to the Western Fjords,” as the city calls itself. Yet, one step at a time, following Arjen and Vidar, we had plunged deep into Norway’s spectacular beauty and cultural soul.

And, ahhh, it was good!

Country Walkers covered a portion of Yvonne Horn’s travel expenses.