Getting an introduction to the specialized crafts of Ghana

by Marlene Smith, Livermore, CO

Accra was on fire.

Landing in Ghana late on Christmas night 2008, my husband, Don, and I went immediately to a hotel in the airport area, so we saw little of the capital city, but we could smell it. During the course of our 25-day stay we would become familiar with the smoke. Ghanaians burn a lot; they burn garbage, they burn their forests to make charcoal and they burn off fields prior to planting season.

During the dry season, Harmattan (West African trade winds) frequently blow off the Sahara to the north, but we didn’t encounter them. Instead, the smoke, mixed with red dust from unpaved roads and black diesel clouds from dilapidated taxis and overloaded trucks, formed a dirty curtain over the land.

So why choose Ghana instead of one of Africa’s other more spectacular destinations? For us, though we hoped to get a traveler’s overview of the country, the choice was more personal. Our daughter, Tammi Martin, and her husband, Chris, serve as Peace Corps Volunteers there, and we would be accompanying them on their first chance to familiarize themselves with the country outside of their village on the Afram Plains.

For travelers

Ghana does, however, afford the seasoned traveler unique opportunities.

For the get-there-first traveler, there’s the satisfaction of navigating through relatively uncharted territory. A bonus — the people are friendly and accommodating and speak English.

For others, walking through dungeons of the coastal castles once packed with slaves awaiting shipment to the New World is an emotional experience, no doubt especially so for those with African roots.

Arts and crafts enthusiasts might wish to visit villages specializing in a number of traditional crafts. Kente weaving and fantasy coffins are unique to Ghana. Textile production, brass casting, bead making and woodcarving are just some of the other crafts at which Ghanaians excel.

Those who are birding enthusiasts can train their binoculars on a colorful collection of rare species, and, though there’s not a plethora of big game, wildlife seekers can go on foot to see elephants up close.

A delayed start

Despite months of planning, our foursome’s sightseeing trip got off to a rocky start. Ghana’s national election on Dec. 7, 2008, didn’t produce a majority winner, and a runoff between the two major contenders was set for Dec. 28. Fearing election turmoil, the Peace Corps issued a “stand fast” edict, asking volunteers to stay at their posts until Jan. 2.

Tammi and Chris were allowed to travel to Accra to meet us, but we then had to return to their home in Donkorkrom, the capital of the Kwahu North District of the Eastern Region.

The forced hiatus produced gratifying results, however. From the high school campus where Tammi and Chris live and teach, the short walk into town afforded us opportunities to meet the locals in everyday situations — a rare opportunity for the typical tourist.

We saw a few people riding bikes, but most were on foot and, almost universally, they exchanged greetings in passing. The greeting “Akwaaba” (“Welcome”) characterizes the country, and it was something we heard frequently as folks came across the road to shake our hands and bid us a good day.

The Martins comprise two-thirds of the obruni (white) population of Donkorkrom (a Dutch nun completes the trio), so their presence is conspicuous, as was ours. The third time we visited The Spot for cold drinks, the proprietor automatically brought out a local beer and a cola for Don and me.

Along the way, Tammi and Chris stopped to chat in the local Twi dialect, and though villagers sometimes laughed at their imperfect pronunciation they obviously appreciated the effort.

After the final election results were further postponed, the opposition candidate, John Atta Mills, eventually was named winner and the ruling party peacefully turned over power. By Jan. 5 we were ready to pursue our now-crunched, “Ghana light” itinerary.

Catching up to our car

Alas, despite our desperate efforts to get off to a fast start, our tour began in typical Ghanaian fashion. The driver and car we procured for what we considered the princely sum of $150 per day plus fuel were to come from Accra to pick us up as early as possible.

Instructions to both the driver and the agency were explicitly given: cross Lake Volta at Adwoso. A call at 8:15 a.m. assured us the driver was at the ferry crossing, except he had decided to ignore the bit about Adwoso and take a short cut. He was at a crossing with a ferry that hadn’t operated in months.

After further missed connections, we bought a phone card which put us in contact with the rental agency. We were told to take a taxi to the nearest town and wait to be picked up in a deserted bus lot. Three hours later it was getting dark and even the woman who’d sold us bananas was getting anxious, returning to our bench to offer to help find us a taxi.

At last our driver called to say he was driving into Nkawkaw, where we were waiting. We spent the next half hour standing by the road while he drove around town looking for four obrunis. A helpful trucker ultimately took our phone and guided him in.

Four service station stops later (the first three were out of diesel), we gave up and asked to be taken to a nearby hotel in the hills above Nkawkaw. We’d gone less than two miles in our rental car.

This long saga is reported here only because it appears to be typical. We heard worse stories from other travelers. On the good side, once we got going, we traveled in a Toyota Land Cruiser in excellent condition with a driver, Eric, who couldn’t follow maps but was friendly and adept at handling the vehicle.

Back on track

After our frustrating day, the Rojo Hotel (phone 0842 22221) was an oasis of calm. We dined poolside on pork cutlets with mushroom sauce and jollof rice (about $10.50). The hotel had AC and hot water, and, in lieu of turndown service, an employee circled the room spraying for insects. The room cost was $50.

The next morning we made it to Koforidua, our intended first night’s stop, in time to brunch on waakye, a popular Ghanaian dish of rice and beans.

After visiting the market we headed for Odumase-Krobo, where a short drive down a side street brought us to the attractive compound of Cedi Beads. Combining a US education with a family tradition of bead making, owner Nene Nomada has created a model for Ghanaian entrepreneurs, one which employs 24 people. We were welcomed hospitably and given a tour and a demonstration of bead making.

From the 14th to the 16th centuries, beads served West Africa as currency. In reverence for this heritage, the bead works recycles antique beads along with making new beads from clay and recycled glass. Though the processes of early bead makers were kept secret, Cedi assures that the modern tradition will be handed down, maintaining ties with several US universities and accepting international students, offering them room and board on site.

Chris, who is on sabbatical as an associate professor in the College of Design at Iowa State University, is interested in compiling a guidebook on Ghana’s artists and craftsmen, so our next stop was the village of Tafi Abuipe in the Volta region, which the Ewe people claim is the birthplace of the art of kente weaving.

The click of shuttles could be heard throughout the village as 300 weavers, some as young as seven, practiced the art of weaving 5-inch strips of cloth into different combinations of traditional patterns. While females aren’t prohibited from weaving, all but one of the weavers we saw were male. Domestic duties occupied the women and girls.

At the Mountain Paradise Lodge (phone 020 813 7086, www.mountainparadise-biakpa.com) in the beautiful Avatime Hills between Fume and Vane, Don and I stayed in a room with shared bath for 20 cedis (about $14.40) while Chris and Tammi opted for a tent on the terrace for 14 cedis. The Mountain Paradise wouldn’t win any stars for facilities, but the view was spectacular.

Woodworkers

In the mahogany-rich area around Asikuma, casket making appeared to be a major industry, with rows of glass-front shops displaying their wares. Not being in the market for a casket, Chris and Tammi purchased a pair of drums from a local maker.

In Agomanya, the twice-weekly market (Wednesday and Saturday) teemed with colorful food and crafts. It’s a major bead market, so we added to our growing collection, but we couldn’t resist also selecting a pineapple, which proved as sweet and juicy as any we’d ever eaten.

A long line of woodcarvers’ stalls lined the road near Aburi. We chose a carving which, until we started packing for the trip home, seemed of modest size. It didn’t fit in any of our luggage, but, after we paid five cedis for shrink wrapping, British Air tolerantly accepted it at no extra charge.

Arriving in Accra, we sought out the fantasy coffin makers on Labadi Road. The fantastically shaped coffins give clues as to the vocation, interests or aspirations of the person for whom each is made. Luxury autos seemed popular. Among other shapes on display were a rooster, fish, banana and chili pepper.

Eric Anemy, whose grandfather first conceived the notion in the 1950s, took time out from working on a whistle-shaped coffin (the final resting place of a referee) to visit with us.

In Accra we stayed at The Paloma (phone 021 228700) for $90 including breakfast. This a full-service hotel, which was fortunate because we were forced to stay there an extra night when I came down with a bout of the “Ghanaian gallop,” necessitating yet another change in itinerary.

Back on the road, we, unfortunately, had to cross Kakum National Park and Elmina Castle off our list and headed straight for Cape Coast Castle, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Our guide showed us the dark, airless dungeons where slaves were kept closely packed prior to shipment by the British, and he pointed out the line to which human waste would reach before any cleanup began. In contrast, we were then taken to the airy governor’s quarters with its excellent view of the harbor.

Ecotourism

Continuing along the coast, we came to Safari Beach Lodge (phone 024 665 1329, www.safari beachlodge.com), an ecotourist venture opened two years before by a couple from Texas. Our gourmet dinner there consisted of escargot, fresh-caught yellow jack in coconut sauce and mashed pumpkin with pineapple, ending with double chocolate cake. Two entrées with shared appetizer and dessert cost about $21. Our bungalow cost $40 per night.

The next day we ventured down the beach for two nights at another ecotourist spot, Green Turtle Lodge (phone 024 489 3566, www.greenturtlelodge.com), a destination well known to backpackers and Peace Corps Volunteers, who pay a bargain rate of 26 cedis ($19) per night.

The food served was good and reasonable, and the bungalows, which had showers and self-composting toilets, were well designed, their architecture funky.

Sadly, the grounds were neglected. There weren’t many palapas (thatch-roofed open-sided structures), and the existing ones needed rethatching. Instead of lounges, there were decaying reed mats and filthy, ragged cloth-covered pillows.

Turtle nesting season had passed and, though we walked the beach at night, the only hatchling we saw was, sadly, in a bird’s beak. Were it not for the refuse washed ashore, the beach would have been superb.

The lodge arranged an enjoyable early-morning ride through the mangrove swamp in a dugout canoe paddled by locals.

Kumasi and north

Veering away from the coast, we spent the next night at Kumasi, the country’s second-largest city and a major crossroad.

Four Villages Inn (phone/fax +233 51 22682, www.fourvillages.com), a small B&B owned by Canadian-Ghanaian couple Chris and Charity Scott, was the most deluxe accommodation of our trip. While living in Canada, Charity had returned to Ghana with a year’s savings each summer for 17 years and worked with the architect and builders to incorporate the best of both cultures. The room cost was $80 per night including a full breakfast.

As we drove north, the climate became drier and the culture more Muslim influenced. Along the way we visited the mosque at Banda Nkwanta, an outstanding example of mud-and-stick architecture.

Mole National Park

Our destination for the night was Mole National Park. With a mere 14,000 visitors per year, it’s still the country’s second-biggest tourist attraction (after the coastal castles). Most people go to Mole for one reason: to see elephants up close and personal, and nearly everyone does.

Mole Motel (phone 027 756 4444), the only overnight accommodation within the park, is situated above watering holes, and it’s often possible to see elephants, several antelope species, crocodiles and birds below. You don’t have to get out the binoculars to see warthogs and baboons; they come calling right to the lodge, as Tammi ruefully discovered when she returned to her room to find baboon footprints on the laundry she’d draped over the balcony.

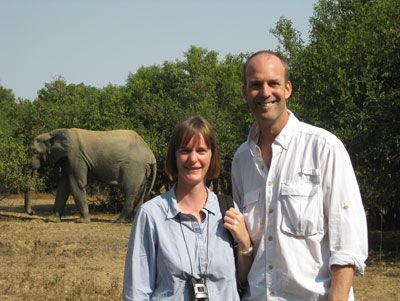

Armed park rangers lead morning and evening nature walks and, though the female and baby elephants had drifted to a remote portion of the park, we were able to get as close to several large male elephants as safety dictated.

Over 300 bird species have been sighted in the park, and, at the visitors’ center adjacent to our motel, we arranged for a combined driving/walking tour (15 cedis per person) with James “Jimah” Coolman, a ranger who’s been observing birds in Mole for over 30 years.

Several of the species he pointed out to us, such as the bright turquoise Abyssinian roller, were spectacular, but most unforgettable was a colony of red-throated bee-eaters which were nesting in a mud riverbank. Arriving shortly before sunset, we found the birds brightly clustered on the tree branches above the river, sharing the bank with an elephant.

Sadly, most Ghanaians never see this national treasure. Most folks’ budgets don’t allow for travel. Eric, our driver, was elated at seeing his first elephant, and we took satisfaction in the small part we played in making it happen.

Hippo sanctuary

The Black Volta River forms the western boundary between Ghana and Burkina Faso, and a portion of the river has been designated as the Wechiau Community Hippo Sanctuary.

Stopping at its visitor center, we arranged for a guide. We opted for the total package: a canoe safari and a night in the hippo hide tree house. The per-person cost was five cedis for admission to the sanctuary, four cedis for the river safari and seven cedis for the hippo ride.

The canoe safari was a success. Flocks of birds flew amongst the lush vegetation lining the shore, and a group of seven hippos floated and bellowed in the river.

We should have stopped there.

After setting up the tree house with foam sleeping pads and mosquito netting for our group of five, which included a volunteer from JICA (the Japanese equivalent of our Peace Corps), our guides left with promises to return the next morning.

As night fell, the river exerted a cooling effect on our lofty perch — actually, a chilling effect. The light wraps we’d brought along proved insignificant; the sleeping bags we use for mountain backpacking would have been more appropriate.

Wherever the hippos went ashore to graze during the night, it was nowhere near our lookout. The only signs of wildlife were birds. The winged creatures we had delighted in seeing during the afternoon became a real pain as they called and cackled all night long. It was like trying to sleep in a refrigerated cuckoo clock factory.

Following the canoe ride back downriver in the morning, we took to the road again for a bone-jarring 7-hour ride back to Kumasi and the Four Villages Inn, where Charity prepared us a delicious 4-course dinner at a cost of $20 each.

Kumasi’s large, crowded and noisy central market isn’t an experience for the faint of heart, but the group was willing to brave the crowd so that I could add African fabric to my quilting stash. Then it was back on the road — dodging potholes, overloaded trucks, livestock, pedestrians and vehicles barreling at us three abreast — for the final leg of our journey back to Accra.

Dinner was pizza at Mama Mia’s, a favorite of expats and affluent Ghanaians.

A guide to the cuisine of Ghana

Ghanaian cooking is based on subsistence, and, since cassava and yams are the main crops, you wind up with a lot of tasteless goo flavored with hot sauce. But sampling the food is an essential part of learning about a country, so here’s a brief guide:

Light soup: A spicy, tomato-based broth is the basis of many meals, along with a side of rice or chips. If you order meat or fufu, it will be served in the soup.

Fufu: If you hear a rhythmic thudding sound when nearing a home, it’s householders pounding cooked cassava or yams with plantains into a doughy ball of fufu. Pinch off a piece of this diet staple, dip it in the soup with which it is served and gulp it down without chewing.

Grasscutter: Providing the most popular bush meat, probably because it’s the most common, these rabbit-sized cane rats are sometimes raised in captivity and often can be seen for sale along the roadside. Served in the light soup, our portions had hunks of thick, tough skin and a length of tail with toothpick-size bones. Yum!

Banku: Fermented maize and cassava, banku is definitely an acquired taste.

Kenkey: When you see locals eating white meal out of a plastic pouch, it’s probably iced kenkey, or ground cassava with ground nuts (usually peanuts) and sugar. Another form of kenkey is fermented, similarly to banku, with a spicy sauce added.

Waakye (pronounced watchee): This is a mixture of beans, rice and macaroni with spicy tomato sauce and sometimes meat, veggies, ground fish or ground cassava added. Think church potluck casserole.

Shitto: This all-purpose red hot sauce usually contains ground fish.

Kelewele: My personal favorite, it’s fried, diced plantains flavored with lime juice, ginger and pepe, Ghana’s version of cayenne.

Convenience shopping

Ghanaians carry everything on their heads. Give a toddler a bagful of anything and up it goes.

If a guy can find a couple of friends to help him hoist a hundred-pound load, he’ll take a couple seconds to balance it, lock his knees and he’s off. It’s a nation of people with excellent posture and extremely strong necks.

People’s heads are also the most convenient place to shop. Superstores pale in comparison.

Hungry? You’ll find trays full of hard-boiled eggs with hot sauce, smoked fish, meat pies, cold drinks, gari (cassava meal), plantain chips, ground nuts or, for dessert, fruit, ice cream or frozen yogurt.

Windshield wiper blades, plastic flowers, lacy lingerie, dress fabric, cleaning products: these are just a sampling of the household products available. I found relief for a nagging cough, and Tammi spotted ant chalk, which friends swear gets rid of the household pests.

Whether you’re at a busy intersection in Accra or on a dirt road in a remote corner of the country, keep your head up and you’ll eventually find what you’re looking for.

Parting tips

For those planning a visit, don’t even think of driving in Ghana. It costs less to rent a car with a driver than without, and just being a passenger is a supreme test of courage.

Although we saw a number of new service stations being built, which should help alleviate the problem, toilet facilities were sparse and Spartan. Most Ghanaians seem to prefer al fresco and they’re matter-of-fact about it. Men don’t bother to step off into the bush to urinate, and locals defecating on the beach, despite our attempts to nonchalantly ignore them, gave a friendly “Hidey-ho!”

Women are frequently garbed in long dresses, allowing them to be more demure, and they’ve mastered the art of going standing up. Female travelers who’d like to try this are advised to bring a travel skirt and washable shoes.

Lastly, if you don’t know the day of the week you were born, you might want to look it up. It’s a question frequently asked of new acquaintances, and you’ve got a one-in-seven chance of an immediate connection.